|

We all had high hopes of the Lahey review of forest practices. The government accepted Professor Lahey's recommendations and promised implementation. Yet, two years later while some work has been done behind the scenes, substantial progress has not occurred. This reminds Ray Plourde of the scenario in 2010 when the Natural Resource Strategy secured a positive reaction from the Dexter government, but then languished while the DNR bureaucracy conducted more 'studies' and put forward delaying strategies. On August 10th, Shelly Hipson gave Louise Renault of CBC a run-down of 'progress' to date, and the next day Ray followed up with an interview with Preston Mulligan. Here are links to the two interviews: One key recommendation of the Lahey review, which has not been followed up, was to expand the range of values expressed in the mandating of legislation for forest regulation in Nova Scotia.

Paul Pross offers some thoughts on the values that have been suggested by HFC supporters in a thoughtful essay found below.

0 Comments

Please take 15 minutes to complete the Nova Scotia State of the Forest Survey.

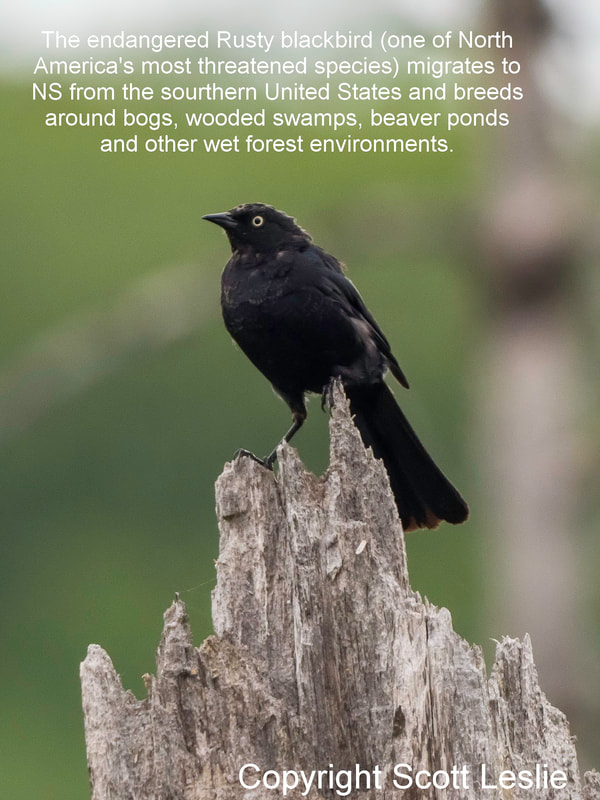

Historically the department has published a resource for all Nova Scotians about the state of our forests. This includes data on Lands, Forests, Forest Ecosystem Health, Forest Conservation, Biodiversity in Forests, Soils and Water, Productivity, Quality, and Value, and Resource Sustainability. The department is working to improve the State of the Forest report by asking Nova Scotians, such as yourself, to complete this survey in the hope that we can better understand how to improve our report to meet your needs. This work was also part of the recommendations in the 2018 Independent Review of Forestry Practices. Thank you for your time! May and June 2020 This Spring brought a notable step forward in our campaign to reform Nova Scotia’s forest policies, but also frustration and disappointment. On May 29, 2020 Judge Christa Brothers, of the Nova Scotia Supreme Court, brought down her decision in the Species at Risk case in which Bob Bancroft, the Federation of Nova Scotia Naturalists, the Blomidon Naturalists Society and the Halifax Field Naturalists accused the Department of Lands and Forestry (LAF) of ignoring its responsibilities under the Species at Risk Act. (The case is formally called Bancroft vs. Nova Scotia (Lands and Forestry) 2020 NSSC 175. It is available at: decisia.lexum.com/nsc/nssc/en/item/479814/index.do Essentially Judge Brothers confirmed what HFC supporters have been saying for a long time: That the government has not enforced the Endangered Species Act. As Jamie Simpson succinctly put it: "The Minister (in reality, the Department) has not fulfilled some of his legal obligations under the Endangered Species Act. Specifically, with respect to the 6 representative species we chose:

This decision requires that the Dept. of Lands and Forestry (LAF) must carry out these duties. Judge Brothers did not impose the timelines that the naturalists requested, so we may continue to see delays, but the essential fact is that the DLF must fulfill its legal responsibilities, not only in relation to the species that were cited in the case, but with respect to all the species covered by the Endangered Species Act. More generally the decision is a severe rebuke to LAF. It addresses Professor Lahey’s criticism that the Department has given priority to its responsibilities toward the forest industry at the expense of the other values that we all associate with the forests. Perhaps Judge Brothers’ refusal to impose the deadlines that the naturalists asked for is a blessing in disguise as it can encourage us to press LAF to develop and implement the recovery plans that the ESA calls for. Under section 21 of the Act the LAF is required to provide certain information to ‘persons’ who ask. That includes copies of status reports, recovery plans and management plans and also copies of the advice given the Minister by the Species-at-Risk Working Group. The more we press the LAF for answers, the more likely it is that real action will be taken. While the decision in the SAR case was hugely satisfying to everyone who has been involved in the forest policy reform campaign, other developments were disappointing or downright frustrating. Discussions revolving around the implementation of the Lahey report are moving so agonizingly slowly, the trees themselves seem to grow more quickly. Many of us wonder whether/when the talks finally end if there will be any trees left to worry about. Perhaps Shelly Hipson expressed it best in her letter to Minister Rankin: "Your department is not implementing Ecological Forestry. They are implementing High Production Forestry (HPF) on potentially a land base larger than the entire Bowater land. The proposed and approved harvests speak for themselves. I have added up the even-aged/clearcut treatments proposed by your department for the past two years from June 2018 to May 2020 and it totals over 46,000 acres. 46,000 acres of clearcuts and not one Irregular Shelterwood – that’s exploitative forestry. Stalling and approving more and more destructive forestry treatments...all under the guise of the Lahey Report. Now the focus is on HPF that is potentially 333,000 hectares of which only 13,000 hectares is non-forested vegetated alders and old fields.

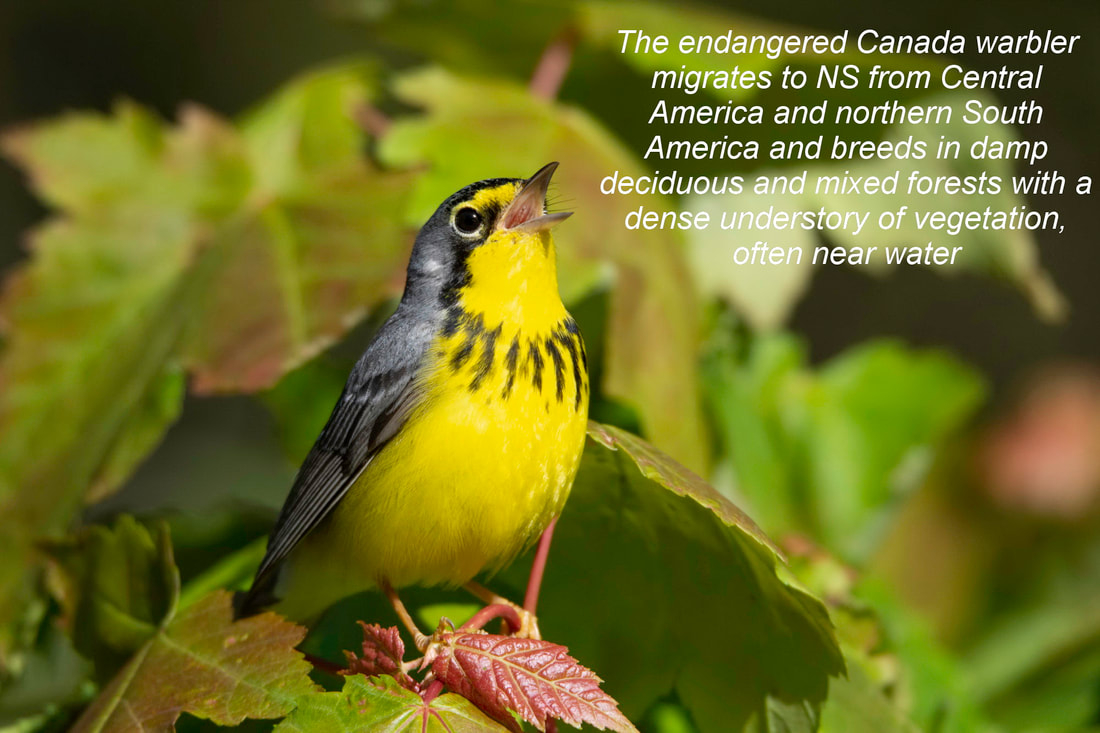

And you say you are implementing ecological forestry? Show me how that is being done IN THE WOODS. Your department might be implementing it behind a desk – but not in nature. Because we ain’t seein’ it. And seeing is believing. And you didn’t answer my question: Removing 90% of a forest. Do you ever think about the wildlife that is living there? Only leaving 10% for them. Isn’t that a tad bit greedy? Regards, Shelly Hipson Nina Newington followed up with a superb interview with Mother Marion on the Diocesian Environment Network IT'S HIGH TIME FOR A SILENT SEASON IN NOVA SCOTIA:Lastly, this year, as with last year, nesting birds were a cause for worry as harvesters moved into previously designated cutting areas. On May 29 Bev Wigney put the following up on the Annapolis Royal & Area Environment and Ecology FB page. It also went to the Nova Scotia Bird Protectors group, and Mike Parker shared it on Woods & Waters: Over the next few days, you'll be hearing more about the need for a SILENT SEASON to be established here in Nova Scotia. What that means is that there would be a "time out" during peak bird nesting season -- an official period of time when forestry MUST CEASE its logging operations to allow birds to nest and raise their young so that they are fledged and ready for their impending fall migration. No longer should they be subjected to being disturbed and destroyed by forestry operations. Other creatures would also benefit from this quiet time - mammals could raise their young without being terrorized by loud machinery hacking down the forest around them. Young amphibians in vernal pools and streams in forests would have a chance to develop before being pulverized beneath the wheels of heavy equipment. Turtles would be less likely to be crushed as they cross roadways to make their way to nesting sites to lay eggs. It would be a WIN for all creatures. It would also help to prevent devastating fire events like the one that happened earlier this week and doubtless left many nests, eggs, and birds charred amongst the smoking carnage. What can you do? NOW IS THE TIME TO SPEAK UP!!! It is important to send a clear message to the politicians of this province that we are FED UP with the lousy way that nature is being treated. WE WANT CHANGE NOW! Not NEXT YEAR or the year after. THAT'S NOT GOOD ENOUGH. What all of us need to do is start sending emails, letters, making phone calls, writing to news websites, posting on social media, and doing whatever else we can to say, NO MORE! NO MORE DESTRUCTION! Please join me in sending emails over the coming week as you hear more about the call for a SILENT SEASON in the forests of Nova Scotia. PLEASE SHARE THIS MESSAGE!!! Shelly sent her message to all the members of the Legislature. Gradually those folks are getting the message. Let’s keep it up!  Every spring we welcome back literally millions of our feathered friends to Nova Scotia's forests. Birds of every shape, size, and colour appear at this time of year as though conjured out of thin air by the lengthening daylight. They herald the re-birth of a winter weary land as they fill with colour and song the tens of thousands of hectares of what remains of our industrially ravaged forests. All manner of them, from the tiny ruby-throated hummingbird to brilliant warblers to birds of prey, return from distant points in the hemisphere to find a breeding territory that for some species may be smaller than an acre. Many songbirds, though tiny enough to fit comfortably in the palm of a small child's hand, have made a perilous journey of thousands of kilometres from their wintering grounds in South and Central America, the Caribbean, Mexico or the southern US to get to Nova Scotia. When they arrive, they are hungry and thin from the near ceaseless activity of the long-distance flight. Yet, when they arrive they must find food, then begin the equally hard work of nest building, laying and incubating eggs, feeding and finally fledging their young. That they have succeeded in doing this for countless generations should inspire our admiration and respect for these amazing creatures! Yet, all is not well for these wonders of nature. Many of them finish the arduous trip north every spring only to find their home has been destroyed: the forest where they bred in previous years has been cut down while they were away over the winter. Even if this tragedy is averted, these newly arrived birds, along with their nests and their young, can be destroyed by commercial logging as they sit on the nest. That's because many loggers, among them large Nova Scotian companies, apparently pay no attention to federal and international law. The Migratory Birds Convention Act is meant to protect migrant birds during the sensitive breeding season. It states that it is illegal to destroy, disturb or harass birds or their nests during breeding season. But this law is not enforced at either the federal or the provincial level. Most logging used to take place in the winter. These days, huge machines clear cut forests, day and night, year round. To protect nesting birds effectively, we need a ‘silent season’ in the woods. That means no logging during breeding season. Countries around the world are adopting this practice. Here in Canada we need wider reform of forestry practices to reflect the incredible value of our forests, not just as an economic resource but as a vital home to biodiversity, so crucial in making the planet liveable for all of us. Let’s start by giving the birds a break. Scott Leslie is a professional wildlife photographer and writer who lives near Smith's Cove, Nova Scotia. He is an author of several books on nature, including a four-volume set on the birds of North America. His photography is represented by National Geographic Image Collection, among others. Our March 9 briefing note to MLAs discusses biomass issues. For a full explanation of the reasoning behind the note, please read the attached letter, titled "Letter to Jason Hollett, et. al. and Mr. Hollett's reply.

Recently there have been some excellent articles published in the Chronicle Herald highlighting some of the missteps of previous and current governments with respect to forestry policy. If you want to better understand why roughly 90% of forestry done in Nova Scotia is done by clear-cutting and why NS taxpayers will never stop paying for Northern Pulp's cleanup bills read on. Oh and in case you hadn't heard, the report for the Independent Review of Forestry Practices in Nova Scotia being conducted by Bill Lahey, and others, was due this past Wednesday, February 28th, BUT, it was given a 2-month extension and the report is now expected by late April.

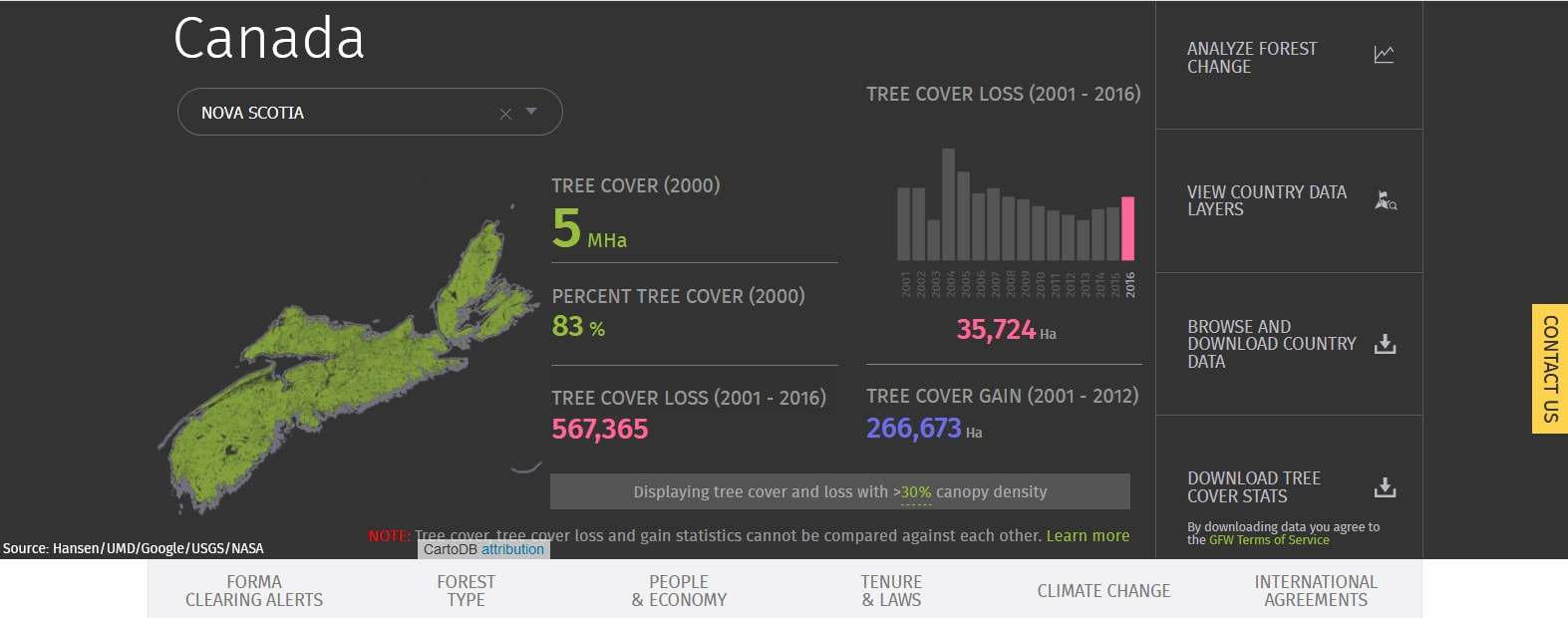

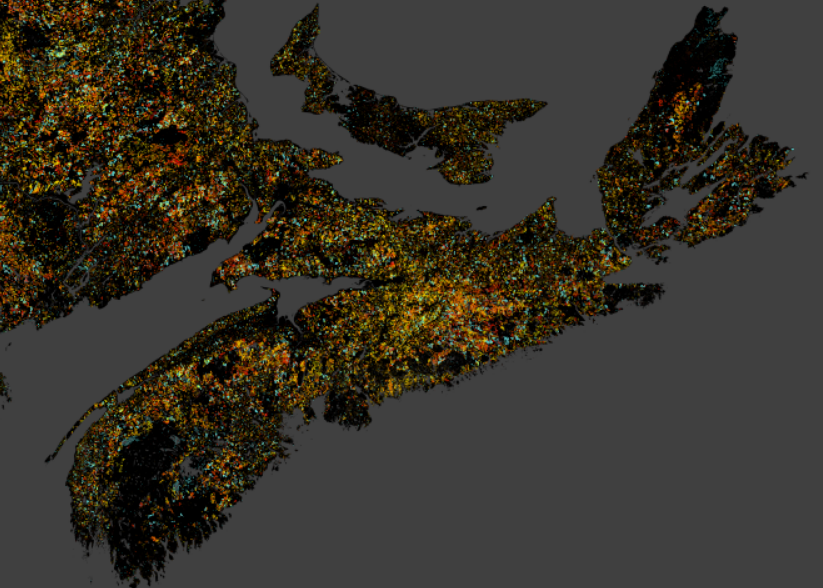

Global Forest Watch (GFW) is an online platform that provides data and tools for monitoring forests. By harnessing cutting-edge technology, GFW allows anyone to access near real-time information about where and how forests are changing around the world. Here at the HFC we'd like to encourage all Nova Scotians to explore this mapping technology and see what is happening in Nova Scotia, your county or even very near your own backyard! You can even get customized reports for specific countries or even provinces! See the screenshot below! Another great site that tracks forest cover loss and gain is hosted by the University of Maryland. It tracks the loss of forest cover since the year 2000.

Although we dealt with significant challenges during our first year, in this, my final report, I am not going to discuss them at length. Rather, I will concentrate on the challenges of the future, looking back at the first year only where our experience then helps us to understand and deal with the issues that are emerging. The first year: Setting up, finding a voice and making a mark Helga got us going. Her biomass petition crystallized concern and brought us together. We had difficulty deciding on how we would operate, eventually deciding against formal organization. We opted instead to rely on social media to activate strategies decided on by a core group. This group has been larger than one usually finds in formal organizations, and it made decisions with very few meetings but a great many emails. We found a voice in identifying and articulating an issue that deeply concerns the people of this province. We have the privilege of living in a beautiful place. Our awareness of this sometimes makes Nova Scotians smug, but it also imposes on us a sense that we must be responsible for maintaining the treasures we have inherited. It induces a conservatism that abhors the waste that is endemic in modern forest harvesting practices. HFC gave voice to this. Public meetings articulated the sense of stewardship that comes with our conservatism. We put these views on line. We wrote letters and op eds that carried the message to the reading public. We made numerous visits to MLAs, in their offices and on the hustings. I cannot name all of you. It was a group effort. Together we helped to make clearcutting an issue in the recent election. The hard part We made a mark. A large public agrees with us. Politicians are aware of what we are saying. Some sense opportunity; others are apprehensive. A good many, torn between the influence of mills owners and the cries of rage, frustration and despair from rural Nova Scotians, have not decided which way to jump. The election is over. The government will soon recover from the minor scare it got in its rural power base. It will succumb to the flattery of the mill owners, whom it considers the real ‘stakeholders’ in our forest economy. Those stakeholders will use the media to reassure the public. The forest bureaucracy in DNR will be more obdurate than ever. All of this will abet the forces of inertia and cynicism that are the bane of modern democracy. How can we fight it? The hardest part will be to keep going. We hear a lot today about ‘the lobbies’ and their ability to influence, even control, democratic governments. Too often, the public, represented by groups like ours, is beaten back simply by the capacity of business lobbies to outlast us. Business can overwhelm us with TV ads, spin doctors, carefully chosen ‘good works’ and cynical exercises in public consultation because businesses are organized to persist. Business leaders come and go, there is always someone to replace those who leave. The costs of lobbying can be written off as ‘business expenses’, which means that we taxpayers help to pay to be fooled. We can beat this. We are on the right side of this issue. Public opinion is shifting in our direction. Elsewhere groups like ours have helped to bring about changes like the ones we propose. We can too. Our greatest strength, and our greatest weakness, lies in the way we carry out our work. We have chosen to avoid formal organization. This has given us the flexibility needed to seize opportunities as they emerge and has forced us to engage our supporters in designing and carrying our campaign. This sense of empowerment is vital and we must make sure that it continues. At the same time it is difficult to be effective if our leadership is scattered and variable and if the members in our project teams don’t carry through on the projects that they have committed to. Over the last year I have thought a lot about this tension in our organizational design. I hope that the following suggestions will help HFC to keep going, to keep on pressing government and forest companies to reform. Have a leadership team: In a social media group, the job of coordination is too big to be managed by one person. It needs a small team. Small enough to work well together. Ensure accountability: When team members, whether of the leadership team or of project teams, undertake a task they should know that they will be expected to complete it, or to see that someone else completes it, within an agreed upon time. The commitment would be made to other members of the team and, through our regular update reports, to the group as a whole. Allow team roles to vary: Traditional organizations have clearly, usually rigidly, defined roles. Part of HFC’s flexibility stems from the fact that we don’t have precisely defined roles. Instead we have tended to encourage members to vary their activities according to their talents, interests and the nature of specific tasks. This has been useful and should be encouraged. It recognizes that everything that pertains to one aspect of our work, also pertains to everything else. It grows out of the fundamental holistic perception of the world that pervades ecological thinking. However, when undertakings are agreed to it is important to be clear about who is going to do what and what is expected of the undertaking. Keep in touch: I spent a lot of time corresponding with HFC members and supporters. Some of you felt that it took too much of my time, and that ‘coordination’ could be done far more efficiently. You may be right. However, there isn’t much holding social media organizations together, beyond a common interest and social interaction. In our case we have a common interest in restoring biodiversity to our forests. It is an interest that flares intensely at times, but can easily be smothered by public indifference and the government inertia that resists change. Correspondence allows supporters to be engaged and shapes a common understanding of the issues that the group is dealing with. It also provides the social interaction that holds the group together. For that reason, I hope that however the group develops at the centre, there will always be someone there whose main task will be to keep in touch with as many supporters as possible. Agree on the message: The evolution of policy has many stages. Each stage compels participants to adapt to changes in roles and discourse. We have been going through a disruptive stage in the development of forest policy. As an opposition group we have focused on problems, to the point where public pressure is beginning to force government to change. At some time in the future, government will say to all of us who have been critical: ‘Alright, we admit that there is a problem. What do we do about it?’ When that happens, advocacy groups must be ready to offer solutions and to search for compromise. This will be difficult for us, as it always is for groups that seek reform. We will have to identify and defend core values, and be prepared to compromise on others that seem less important. In opposition we have been able to ignore differences between us concerning some core values. As we approach the negotiation stage of policy development, those differences will cause conflict. We want to go into that stage united behind a well thought-out position and with strategies that make the most of our resources. Consequently, the sooner we start thinking about solutions and compromises the better. A glimpse of the big picture: Nova Scotia’s forests have experienced three great periods of growth, development and decline. The Mi’kmaq lived here for centuries as a climax forest developed. Europeans began settlement at the beginning of the seventeenth century, and by the end of the nineteenth had burned or otherwise reduced the climax forest to a point where, in 1912, Bernard Fernow made one of the first calls for reform and restoration. Over the following century the forestry profession, in government and the pulp and paper industry, responded to that call by transforming our Acadian forest into one that resembled the boreal forest predominant in most of Canada. Today, the industry that spawned it has declined, and we must decide what to do with – and for - the forest that remains. The Healthy Forest Coalition has urged a return to biodiversity and, to the extent possible, restoration of the Acadian forest. In order to achieve that we must understand our common cause. We must continue to speak up, and refuse to be discouraged. We must adapt as we push forward the processes of negotiation. We must persist. Paul Pross, HFC Coordinator, March-April, September 2016-June, 2017.

CBC's Michael Gorman throws the HFC gauntlet down on WestFor's path to an unheard of 10-year lease. The 13 mill consortium has their eyes on the people of Nova Scotia's Western Crown Lands, that is the lands we bought back from Bowater-Mersey in an effort to change the way forestry is practiced in this province. Fat chance. The DNR and its Minister Hines seems bent on granting WestFor's wishes. Check out Gorman's take here.

|

Blog Archives

October 2020

Blog Index

All

|

||||||

Photo used under Creative Commons from DaveW99999

RSS Feed

RSS Feed